Tourmaline Gem, Price, and Jewelry Information

Discover tourmaline's stunning colors, value, and properties. Learn why this October birthstone makes exceptional jewelry and how to identify genuine tourmaline varieties.

17 Minute Read

Tourmaline represents an extraordinarily diverse gemstone family with properties that make it a jewelry favorite. This modern October birthstone appears in virtually every color imaginable including pink, green, blue, black, and watermelon varieties. With its durability and rainbow of hues, tourmaline combines beauty and versatility in a way few gemstones can match.

Start an IGS Membership today

for full access to our price guide (updated monthly).Tourmaline Value

In this comprehensive guide to tourmaline, you'll learn:

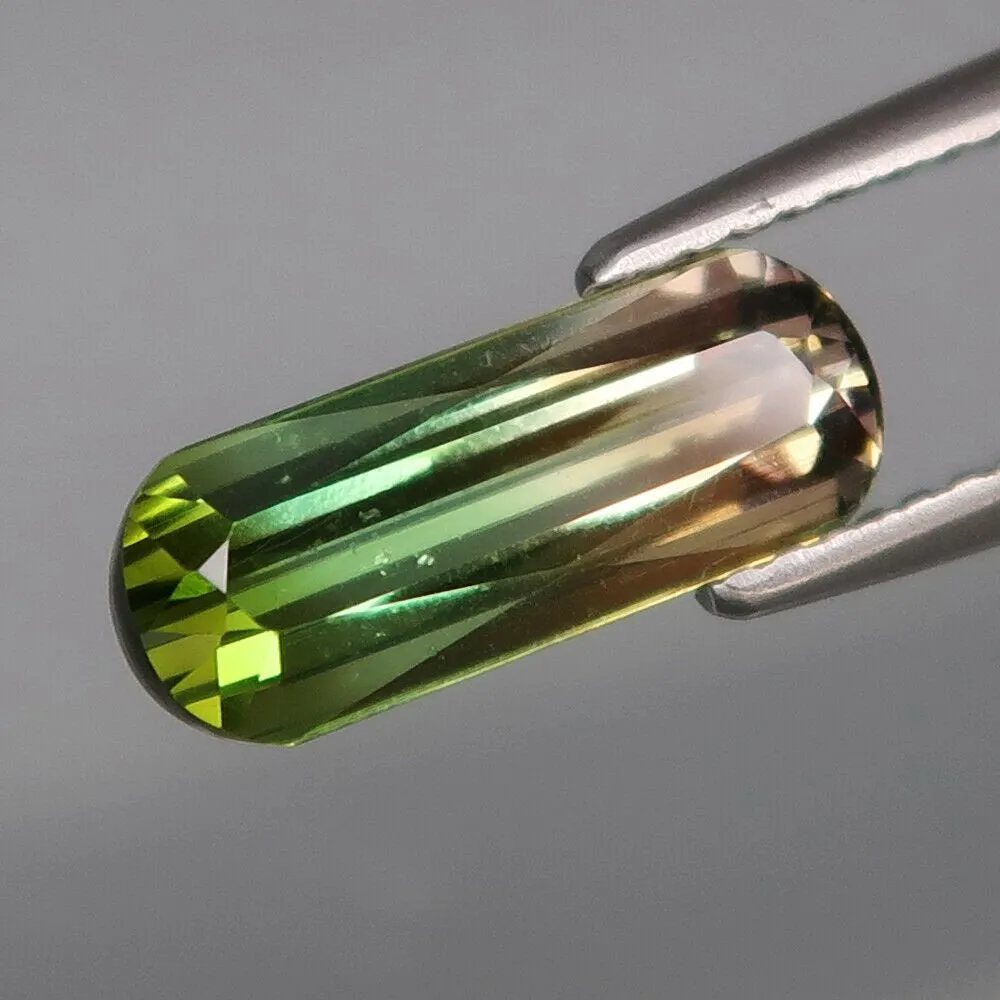

- Tourmaline comes in more color varieties than almost any other gemstone, including rare multi-color patterns that create stunning visual effects.

- The value of tourmaline varies significantly based on color, clarity, and origin, with certain varieties commanding premium prices.

- Tourmaline's excellent durability (7-7.5 on the Mohs scale) makes it suitable for everyday jewelry wear across all settings.

- How to identify genuine tourmaline stones and recognize the different varieties in the marketplace.

- Proper care techniques to maintain your tourmaline jewelry's beauty for generations.

What is Tourmaline? Understanding the Gemstone's Composition

Tourmaline constitutes a mineral supergroup comprising three groups, multiple subgroups, and over thirty distinct species. With ongoing discoveries, researchers continue to expand the list of tourmaline species. All share the same trigonal (hexagonal) crystal structure but feature different chemical formulas.

The Victorian writer John Ruskin's quip from 1890 still applies to tourmalines today:

The chemistry of [tourmaline] is more like a medieval doctor's prescription than the making of a respectable mineral.

The basic formula for tourmaline is:

XY₃Z₆(T₆O₁₈)(BO₃)₃V₃W

In this formula, X, Y, Z, T, V, and W can represent different elements, allowing numerous substitutions and variations. This chemical complexity creates tourmaline's vast array of appealing colors, including the striking multi-color patterns that collectors cherish.

Does Tourmaline Make a Good Jewelry Stone? Durability and Appeal

Tourmaline colors satisfy virtually any fashion requirement. With a hardness of 7 to 7.5, nocleavage, and only slightbrittleness, these gems make excellent jewelry stones for everyday wear.

Additionally, tourmaline crystals occur abundantly worldwide, often in cuttable and sometimes large, well-terminated specimens. These factors keep tourmalines generally affordable and highly popular with consumers.

Artisans also find tourmaline suitable for carving cameos and intaglios as well as crafting all manner of shapes and figures.

How to Identify Tourmaline: Properties and Characteristics

Gemologists consider all members of the tourmaline supergroup as tourmalines. Many species exhibit such similar properties that separating them proves challenging. For practical gemological purposes, simply identifying them as tourmaline suffices.

Distinguishing specific tourmaline species may require advanced gemological tests, like laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS).

Tourmalines possess several distinctive physical properties:

- They are piezoelectric, generating electricity when placed under pressure.

- They exhibit pyroelectric properties, producing electricity when heated.

They develop an electrostatic charge when rubbed.

What Color is Tourmaline? The Rainbow Gemstone Spectrum

Tourmaline crystals occur in every color of the spectrum, including red, yellow, green, blue, pink, colorless, and black. Many crystals feature color zoned patterns along their length (bi-color, tri-color, parti-color) or concentrically zoned (watermelon tourmaline).

This remarkable color range makes tourmaline one of the most diverse colored gemstones in the world, with something to complement any jewelry design or personal preference.

Tourmaline Species: Understanding the Varieties

The vast majority of cut tourmaline gemstones belong to the elbaite species. Other species you might encounter in jewelry include dravite, liddicoatite, schorl, and uvite. You'll rarely find other tourmaline species cut as gemstones, though they occasionally appear.

The following table breaks down the differences in optical and physical properties between various species. (Note that all tourmalines share the same optic character and dispersion. Hardness can vary from 7 to 7.5). The species most commonly found as gemstones appear in bold italic type.

Variations in Properties by Tourmaline Species

| Species | SG | o | e | Birefringence |

| "Buergerite" (fluor-buergerite) | 3.29-3.32 | 1.735 | 1.655-1.670 | 0.065-0.080 |

| Chromdravite | 3.39-3.41 | 1.778 | 1.772 | 0.006 |

| Dravite | 3.10-3.90 | 1.627-1.675 | 1.604-1.643 | 0.016-0.032 |

| Elbaite | 2.84-3.10 | 1.619-1.655 | 1.603-1.634 | 0.013-0.024 |

| Feruvite | ~3.20 | 1.687 | 1.669 | 0.018 |

| Foitite | ~3.17 | 1.664 | 1.642 | 0.022 |

| "Liddicoatite" (fluor-liddicoatite) | ~3.02 | 1.637 | 1.621 | 0.016 |

| Magnesio-foitite | 2.96? | 1.650 | 1.624 | 0.026 |

| Olenite | ~3.01 | 1.654 | 1.635 | 0.019 |

| Povondraite | 3.18-3.33 | 1.820 | 1.734 | 0.057 |

| Rossmanite | ~3.00 | 1.645 | 1.624 | 0.021 |

| Schorl | 2.82-3.24 | 1.638-1.698 | 1.620-1.675 | 0.016-0.046 |

| Tsilaisite | ~3.13 | 1.645-1.648 | 1.622-1.623 | 0.023-0.028 |

| Uvite | 3.01-3.09 | 1.632-1.660 | 1.612-1.639 | 0.017-0.021 |

| Vanadiumdravite | ~3.32 | 1.786 | 1.729 | 0.057 |

Tourmaline Species Descriptions

Buergerite

Although some specimens carry the label "buergerite," the correct name for this tourmaline species is fluor-buergerite. The "W" site in its chemical formula contains fluorine (F). ("Buergerite," with oxygen-hydrogen (OH) in the "W" site, hasn't been discovered in nature).

These rare, dark brown to black crystals sometimes display a bronze-colored iridescence beneath the surface.

Chromdravite

Also called chromium-dravite or chromian dravite, this tourmaline variety contains high chromium (Cr) content. Chromdravite displays an intense, dark green color reminiscent of fine emerald.

Dravite

Dravite tourmalines exhibit variable colors, including yellow, brown, black, greenish black, dark red, pale blueish green to emerald green, and even colorless specimens. This tourmaline species occurs in numerous global locations.

Elbaite

Elbaite represents the most common tourmaline species. It appears in every color of the rainbow and originates from many sources worldwide, making it the backbone of the tourmaline jewelry market.

Feruvite

This rare tourmaline appears in dark brown to black colors and represents the iron member of the uvite subgroup.

Foitite

A bluish black to dark indigo tourmaline with purple tints.

Foitite crystal from Mt. Mica, Maine. The backlighting highlights its purple tints. © Rob Lavinsky, www.iRocks.com. Used with permission.

Liddicoatite

Although "liddicoatite" traditionally refers to tourmalines with complex, multi-colored zoning, these stones may belong to two distinct species. For years, scientists classified liddicoatite as a type of elbaite. In 1977, researchers determined it represented a calcium analogue to elbaite (with Ca in the "X" site).

Later, researchers redefined liddicoatite. Fluor-liddicoatite contains F-dominant elements in the "W" site, while OH-dominant liddicoatite has OH-dominant components in the "W" site. Scientists continue investigating whether OH-dominant liddicoatite exists naturally. Currently, it lacks official species approval. Nevertheless, gemologists and collectors still commonly use "liddicoatite" to describe stones that technically qualify as fluor-liddicoatites.

Magnesio-foitite

This magnesium-dominant variety (with Mg in the "Y" site) of foitite displays greenish brown to blueish gray colors.

Olenite

Olenite tourmalines exhibit colors ranging from blue to pale shades of pink, blue, or green, and sometimes appear completely colorless.

Povondraite

In 1997, researchers determined this rare tourmaline, formerly known as ferridravite, wasn't actually the ferric (Fe3+) analogue of dravite as previously believed. It displays nearly opaque, dark brown, brownish black, or black colors.

Rossmanite

This rare tourmaline species exhibits pink to tan colors that can create attractive gemstones when clean specimens appear.

Schorl

Black schorl tourmaline has adorned jewelry since ancient times. During the Victorian Era, jewelers frequently incorporated schorl into mourning jewelry. Modern jewelry designers seldom cut this common tourmaline into gemstones. Schorl can also occur in brown, blue, or blue-green shades.

Tsilaisite

Scientists first proposed "tsilaisite" as a name for a hypothesized manganese-dominant (Mn) tourmaline species in 1929. In the mid-1980s, discoveries in Zambia of yellow tourmalines with high Mn content prompted some researchers to assert these were natural tsilaisites. Vendors even began using this name, despite lacking official approval and the stones failing to meet the criteria for a new species.

In 2006, researchers determined these stones were merely Mn-rich elbaites and discredited the name. When tested in 2011, more than 200 candidate stones from worldwide sources failed to contain the minimum manganese content (>10.71 wt.% MnO) required for classification as tsilaisites.

However, in 2012, yellow tourmalines discovered in Elba, Italy finally proved to be the elusive Mn-dominant species (with Mn in the "Y" site). This discovery led to the official approval of tsilaisite as a valid tourmaline species.

Uvite

Another revised and re-approved species (in 2020), uvites form a tourmaline subgroup consisting of uvite proper, fluor-uvite, and feruvite. Most specimens labeled as uvite actually represent fluor-uvite, the common, F-dominant member (with F in the "W" site).

Uvites display a wide range of colors including black, light to dark green, brown, red, and occasionally other hues, including colorless.

Vanadiumdravite

This vanadium-bearing dravite exhibits dark green to black color derived from its vanadium content.

Descriptive and Trade Names for Tourmaline

Many trade names exist for tourmalines based on color and appearance. While their characteristics may align with specific species, the following names don't designate scientific species. For example, rubellites typically belong to the elbaite species but may also be liddicoatites and olenites. Paraíba tourmalines historically classified exclusively as elbaites until the discovery of copper-bearing liddicoatites with paraíba colors in 2017.

Although "dravite" officially designates a specific species, dealers sometimes apply this name to yellow and brown tourmalines regardless of their actual species.

Achroites

Colorless tourmalines, often highly valued for their rarity and pristine appearance.

Canary Tourmalines

Bright yellow tourmalines that display sunny, vibrant color reminiscent of canaries.

Cat's Eye

Chatoyant tourmalines that exhibit the eye effect in various colors, created by parallel hollow tube inclusions.

Chrome Tourmalines

These intense green tourmalines derive their color from chromium or vanadium content. Tourmalines colored green without chromium or vanadium receive the name verdelites.

Color-Change Tourmalines

Extremely rare tourmalines display a distinct color change between daylight and incandescent light conditions.

Some tourmalines exhibit an Usambara effect, a type of color change that depends partly on the light path length through the stone.

4.57-ct color-change tourmaline, dark green to reddish brown, mixed marquise cut, East Africa. © The Gem Trader. Used with permission.

Indicolites

Blue tourmalines. Specimens with intense, neon-blue colors caused by copper content classify as paraíba tourmalines.

Paraíba Tourmalines

Intense, neon-blue tourmalines colored by copper. Originally discovered in and named after the Brazilian state of Paraíba, specimens have also appeared in Nigeria and Mozambique. The gem community largely accepts the definition of paraíba tourmalines by color and copper content.

However, some dealers reserve the term exclusively for Brazilian material, referring to African material as "paraíba-like" or simply "cuprian blue tourmaline."

Identifying the source of paraíba tourmalines requires quantitative chemical analysis via advanced gemological testing.

Tourmalines with blue colors not caused by copper receive the name indicolites.

Parti-Colored

Tourmalines displaying more than one color, often with striking boundaries between the different hues.

Rubellites

The term rubellite typically refers to tourmalines with reasonably saturated dark pink to red colors and medium to dark tones, from raspberry to ruby-like red. These stones often show strong purplish, orangish, or brownish secondary hues. Jewelers frequently cut rubellites into various shapes that showcase their beautiful color and transparency.

Trapiche Tourmalines

When sliced perpendicular to the c-axis, trapiche tourmalines reveal inclusions formed from organic matter between growth sectors of the crystal structure. These inclusions resemble spokes radiating from the center of a wheel. Although these patterns may appear star-like, they differ from star stones which display asterism.

Verdelites

Green tourmalines without chromium or vanadium content. Stones with deep green color derived from chromium or vanadium classify as chrome tourmalines.

Watermelon Tourmalines

These striking tourmalines feature a pink or red "core" at the center surrounded by a green "rind" or border. Some specimens contain a colorless ring between these two areas. When cut in cross-section, these stones truly resemble slices of watermelon.

Tourmaline Misnomers: Misleading Names to Avoid

Although tourmalines remain popular gemstones, other gem names may carry more prestige and command higher prices. Consequently, some unscrupulous vendors might use evocative but deceptive combinations of gem names to market tourmalines more effectively. For example, you might encounter green tourmalines sold as "Brazilian emeralds" or "Ceylonese peridots" and blue tourmalines marketed as "Brazilian sapphires."

These terms represent unacceptable trade names for tourmalines. Tourmalines, emeralds, peridots, and sapphires constitute distinct gem species. Emeralds and sapphires typically cost considerably more than most tourmalines. To complicate matters, emeralds genuinely occur in Brazil, and peridots do appear in Sri Lanka.

Ask vendors to clarify the names and sources of any tourmalines they sell or request a gem laboratory analysis, especially for high-value gemstones.

Does Tourmaline Show Pleochroism? Color Changes with Viewing Angle

Dark green and brown tourmalines exhibit particularly strong pleochroism, while pale-colored specimens display weak dichroism. Light traveling along the length of a prismatic crystal consistently shows deeper color than when viewed at right angles to this direction.

This dichroic, rectangle-cut tourmaline looks forest green when viewed face up but olive green from the sides. © Rob Lavinsky, www.iRocks.com. Used with permission.

The absorption of the o-ray in tourmaline proves strong enough to plane-polarize light. Sometimes, this ray becomes totally absorbed and a tourmaline may appear isotropic, showing only one absorption edge on the refractometer.

Typical Pleochroic Colors for Tourmaline Species

| Specimen | o | e |

| Fluor-Buergerite | yellow-brown | very pale yellow |

| Dravite | yellow | colorless |

| orange-yellow | pale yellow | |

| dark green | olive green | |

| bluish green | yellowish green | |

| medium to dark brown | yellowish to light brown | |

| Elbaite | medium pink | light pink or colorless |

| green | yellow to olive green | |

| blue-green | light green to purplish | |

| blue | colorless to pink to purple | |

| Povondraite | dark brown to dark olive green | light olive green to light brown |

| Fluor-liddicoatite | dark brown | light brown |

| Schorl | blue to greenish blue | yellow, yellow-brown, pale violet or colorless |

| green-brown | rose-yellow | |

| dark brown | yellow, light brown, or yellowish blue-green | |

| Uvite (like dravite) | ||

| Chromdravite | dark green | yellow-green |

| Tsilaisite | pale greenish yellow | very pale greenish yellow |

What Inclusions Can Tourmaline Contain? Internal Features

Most tourmalines fall under the Type II clarity category, "Usually Included." Green tourmalines classify as Type I, "Usually Eye Clean," while red and watermelon tourmalines belong to Type III, "Almost Always Included."

All tourmalines may contain inclusions of hollow tubes—elongated or irregular thread-like cavities, sometimes containing liquid or gas inclusions, occasionally two-phase inclusions—often in mesh-like patterns. These tubes typically run parallel to the crystal length and, when densely packed, may create a chatoyant effect in cabochon-cut stones.

Red tourmalines frequently contain gas-filled fractures and flat films that reflect light and appear black under magnification.

Tourmalines may also contain mineral inclusions such as:

What is Tourmalinated Quartz? Tourmaline in Quartz

Some clear quartz stones contain needle-like inclusions of black tourmaline crystals. Called tourmalinated quartz, these pieces create attractive display specimens and fascinating gemstones for jewelry.

Tourmaline Value: What Determines Price and Quality

Tourmaline's reasonable availability keeps prices accessible for most buyers. Small tourmaline stones under 5 carats remain fairly easy to obtain at modest cost. Prices typically exceed a few hundred dollars per carat only for large sizes or exceptionally rare colors.

While most tourmaline colors appear commonly, pure blue, red, orange, yellow, and purple stones command higher prices due to their rarity. Collectors and connoisseurs especially prize these exceptional varieties:

- Neon-blue paraíba tourmalines contain copper and display electric colors unlike any other gemstone.

- Raspberry-red rubellites offer rich, saturated color that rivals fine rubies.

- Emerald-green chrome tourmalines present vivid color from chromium content.

Tourmaline crystals frequently contain cracks and flaws, creating premium value for clean gemstones, particularly those exceeding 10 carats. The most acceptable inclusions in cut tourmalines are hollow tubes that, when densely packed, produce a cat's eye effect in cabochons. These cat's eye tourmalines can display remarkably strong chatoyancy against richly colored backgrounds.

For more detailed information on quality factors, consult our buying guides for tourmalines in general and engagement ring stones.

You may also wish to read these specialized guides for specific varieties:

- Chrome Tourmaline Buying Guide

- Green Tourmaline (Verdelite) Buying Guide

- Rubellite Tourmaline Buying Guide

- Blue Tourmaline (Indicolite) Buying Guide

- Paraíba Tourmaline Buying Guide

- Watermelon Tourmaline Buying Guide

Is There Synthetic Tourmaline? Lab Creation Facts

Scientists have produced synthetic tourmalines for research purposes. For example, before the discovery of natural tsilaisite, researchers created it in laboratories (1984) along with other Mn-rich tourmalines (2003). However, no commercially available lab-created tourmaline exists for gem or jewelry use.

In 1993, Russian scientists synthesized tourmalines via a hydrothermal process, growing synthetic tourmaline over natural tourmaline seed crystals. In 2008, the International School of Gemology (ISG)—not the International Gem Society (IGS)—concluded that some unusual tourmalines it acquired likely represented synthetics manufactured similarly to those in the 1993 experiment. As news of that declaration spread, rumors circulated that synthetics had entered the gem market.

Stone Group Labs' Bear Williams debunked this rumor. In his 2009 article, he noted that the 1993 experiment produced only minuscule amounts of synthetic tourmaline at tremendous cost. Furthermore, he observed that the ISG made errors comparing the Raman spectroscopy of its specimens to those examined during the 1993 research. In a response, the ISG reported it had reevaluated its tourmaline specimens and determined they were actually natural liddicoatites, not synthetics.

Synthetic tourmaline remains expensive and difficult to create with no economic incentive for commercial production. Inexpensive yet gem-quality natural tourmalines remain readily available. Although you might find "simulated" tourmaline for sale online, careful reading reveals this term often means "fake" rather than lab-created tourmaline.

What Treatments Do Tourmaline Gemstones Receive? Enhancement Methods

While synthetic tourmalines don't exist commercially, natural tourmalines frequently receive enhancements. These treatments can improve low-quality stones' appearance and color or transform natural colors into more attractive (and valuable) alternatives.

Common tourmaline treatments include:

- Heating: Lightens blue and green stones; common, stable, undetectable. Can occasionally produce other colors; stable and undetectable.

- Irradiation: Produces red, deep pink, yellow, orange colors, and parti-colors; common. May fade with heating or prolonged exposure to bright light; undetectable.

- Acid treatment: Bleaches dark inclusions, primarily in cat's eye specimens; occasional, stable, undetectable.

- Plastic or epoxy fillers: Seal hollow tubes to prevent dirt infiltration; occasional, stable. Detectable with hot point test and magnification.

- Dyes and coatings: Usually unstable and not recommended.

Where is Tourmaline Found? Global Mining Locations

The following sources represent major tourmaline producers, and the listed varieties include some of the most notable from each location. Many sources also produce additional tourmaline varieties beyond those mentioned. Numerous other sources not listed also yield tourmalines.

Afghanistan

At Nuristan, superb gem elbaite in shades of blue, pink, green, and even emerald green.

Bolivia

At Cochabamba, povondraite.

Brazil

In Minas Gerais and other states, usually elbaite, in a huge variety of colors and sometimes large crystals; also bi-color, cat's eye, watermelon tourmaline. Especially noteworthy are the immense cranberry-red crystals from the Jonas Lima Mine and the superb dark-red material from Ouro Fino.

Czech Republic

At Strázek Moldanubicum, rossmanite.

India

At Kashmir, green elbaite crystals. RI 1.643, 1.622; SG = 3.05, birefringence = 0.021.

Japan

At Honshu, magnesio-foitite, rare.

Kenya

Fine, deep red and other colors. The red is dravite; (also yellow shades). The following table describes their properties.

e | o | Birefringence | SG | Color |

1.623 | 1.654 | 0.031 | 3.07 | red |

1.626 | 1.657 | 0.031 | 3.08 | red |

1.619 | 1.642 | 0.022 | 3.04 | yellow |

Malawi

Canary tourmalines.

Madagascar

Liddicoatite (previously thought to be elbaite) in a huge range of colors, shades; crystals often concentrically zoned with many color zones, triangular in outline; many crystals very large. Also, fine rubellite.

Mexico

Buergerite occurs in rhyolite at San Luis Potosí, rare.

Mozambique

Paraíba (cuprian) tourmalines. At Alta Ligonha, pale-colored elbaite in various shades; bi-colors.

Myanmar

The Mogok area produces red tourmalines, also some pink elbaites and brown uvites.

Namibia

- Usakos: fine elbaite of rich green color (chrome tourmaline).

- Klein Spitzkopje, Otavi: tourmaline in many shades of green and other colors (elbaite).

New Zealand

Feruvite found at Cuvier Island, rare.

Nigeria

Paraíba (cuprian) tourmalines and other varieties.

Russia

- Mursinka, Urals, also at Nerchinsk: blue, red, and violet crystals in decomposed granite.

- Central Karelia: chromdravite (dark green).

- Kola Peninsula: olenite, rare.

Scotland

At Glenbuchat, Aberdeenshire, color-zoned elbaite up to several centimeters, suitable for cutting.

Sri Lanka

Yellow and brown crystals. This is an ancient source of gem tourmaline, now known to be uvite rather than dravite.

Tanzania

Elbaite containing Cr and V, resulting in rich green shades.

United States

- California: elbaite in abundance at Pala and other localities, in both fine crystals and gemmy material. The pink elbaite from here is a unique pastel shade. Also, blueish black foitite, uncommon.

- Connecticut: at Haddam, elbaite in small but fine crystals, color-zoned.

- Maine: at Newry, huge deposit of fine elbaite, with exquisite gem material in green, blue-green, blue, and pink to red colors.

- New Jersey and New York: at Franklin and Hamburg, New Jersey, and at Gouverneur and DeKaIb, New York, uvite crystals, some with gem potential. This material had always been regarded as dravite.

Zambia

At Chipata, dark red crystals similar to Kenyan dravite. RI 1.624-1.654; birefringence = 0.030; SG = 3.03-3.07 (average 3.05). Also gemmy yellow material with up to 9.2 wt. % MnO, very rare. Also, trapiche tourmalines.

Zimbabwe

In the Somabula Forest area, fine elbaite.

Other Notable Tourmaline Sources

- China; Democratic Republic of the Congo; Italy; Nepal; Pakistan; Tajikistan; Vietnam.

Stone Sizes

Tourmalines weighing hundreds of carats have been cut out of material from various localities. Brazil and Mozambique produce some of the largest stones, but Maine and California have also yielded crystals of very large size. Most larger museums have fine tourmaline collections and display very large gems. (A representative collection of tourmaline colors would have to encompass well over 100 stones).

- Smithsonian Institution (Washington, DC): 246 (pink, faceted egg, California); 116.2, 100 (pink, California); 172.7, 124.8 (champagne color, Mozambique); 122.9 (green, Mozambique); 117, 110 (green, Brazil); 110.8 (pink, Russia); 75 (rose-red. Brazil); 62.4 (pink, Brazil); 18.4 (pink, Maine); 103.8 (rose, Mozambique); 60 (blue-green, Brazil); 41.6 (brown, Sri Lanka); 23.5 (pale brown, Brazil); 17.9 (green, South Africa); 17.7 (yellow-green, Elba, Italy).

- Private Collection: 258.08 (green cat's eye); 256 (green, Maine, very large for locality).

How to Care for Tourmaline Jewelry

Tourmaline rough can challenge even experienced gem cutters. Multi-colored gems are often weak where the colors meet, but all color varieties may have stressed areas. Nevertheless, once cut and set in jewelry, tourmalines are very durable stones.

Tourmaline's Mohs hardness of 7 to 7.5 means these gems can resist scratches from most everyday hazards, including household dust. That's very fortunate, because due to tourmaline's electrical conductivity, these gems will attract more dust than non-conductive stones. So, you may have to clean them frequently

Since most tourmalines have numerous inclusions, avoid cleaning them with ultrasonic or steam devices. Vibrations and heat may cause liquid inclusions to expand, shattering the stone. Instead, use a soft brush, mild detergent, and warm water.

Consult our gemstone jewelry care guide for more recommendations.

Joel E. Arem, Ph.D., FGA

Dr. Joel E. Arem has more than 60 years of experience in the world of gems and minerals. After obtaining his Ph.D. in Mineralogy from Harvard University, he has published numerous books that are still among the most widely used references and guidebooks on crystals, gems and minerals in the world.

Co-founder and President of numerous organizations, Dr. Arem has enjoyed a lifelong career in mineralogy and gemology. He has been a Smithsonian scientist and Curator, a consultant to many well-known companies and institutions, and a prolific author and speaker. Although his main activities have been as a gem cutter and dealer, his focus has always been education. joelarem.com

Donald Clark, CSM IMG

Donald Clark, CSM founded the International Gem Society in 1998. Donald started in the gem and jewelry industry in 1976. He received his formal gemology training from the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) and the American Society of Gemcutters (ASG). The letters “CSM” after his name stood for Certified Supreme Master Gemcutter, a designation of Wykoff’s ASG which has often been referred to as the doctorate of gem cutting. The American Society of Gemcutters only had 54 people reach this level. Along with dozens of articles for leading trade magazines, Donald authored the book “Modern Faceting, the Easy Way.”

International Gem Society

Related Articles

Some Advice for Cutting Tourmaline Gemstones

Tourmaline Engagement Rings: the Ultimate Guide

Advice For Grading Dark Colored Gemstones

Chrome Tourmaline Buying Guide

Latest Articles

800 Years of Mogok: A Celebration in Tenuous Times

What is the Average Gemstone Faceting Yield?

Pyroxmangite Value, Price, and Jewelry Information

How to Identify Emerald Simulants and Synthetics

Never Stop Learning

When you join the IGS community, you get trusted diamond & gemstone information when you need it.

Get Gemology Insights

Get started with the International Gem Society’s free guide to gemstone identification. Join our weekly newsletter & get a free copy of the Gem ID Checklist!